- Home

- Helen Fripp

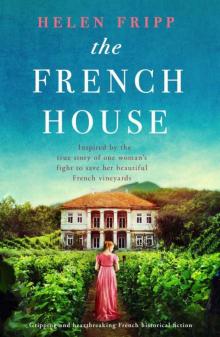

The French House

The French House Read online

The French House

Gripping and heartbreaking French historical fiction

Helen Fripp

Books by Helen Fripp

The French House

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Hear More from Helen

Books by Helen Fripp

A Letter from Helen

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

For Tara and Charlie

Hold fast to your dreams

‘Why should we build our happiness on the opinions of others, when we can find it in our own hearts?’

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Chapter 1

Revolution

Reims, 21 July 1789

Nicole stopped at the crossroads on this glorious morning and considered her choices. Should she take the rue des Filles Dieu, a shaded, godly alleyway for obedient girls leading straight to her convent school, or a forbidden detour across the open square, where the sunlight quivered in a haze above the cobbles?

She flipped a coin, caught it on the back of her hand and shut her eyes. Pile ou face, heads or tails. It didn’t matter – the forbidden square was always going to win, especially on market day. It was the only real choice, brimming with promise, and she ran towards the sunlit square.

At King Louis XVI’s statue, she stopped to pat the stone horse’s weathered muzzle for luck, dipped a mock-curtsey to the king and froze… A noose was slung around the king’s neck. And someone had daubed droplets of red paint under his regal eyes. The king was crying blood! Surely this wasn’t Xavier’s work? He sometimes gave the king a charcoal moustache or stuck a geranium under the horse’s saddle to protrude from his arse, but never anything this macabre.

So it must be true then, about the news from Paris. The whole town was simmering with it. Quatorze Juillet, the day France turned upside down. The king discredited. The people’s republic, the revolution. Loud arguments on street corners and endless gossip, all about something miles away. The noose and blood was the kind of thing that happened in Paris, not here in safe, sleepy Reims.

Defacing an image of the king was a serious offence – one the Comte’s soldiers would be sure to punish. They were an undisciplined gaggle of bored thugs who regularly patrolled the streets for someone to beat, including truants, even rich ones like her.

Nicole walked as fast as suspicion allowed to the safety of the square. On market days, the place was usually teeming with champenois farmers setting out their bright stalls like sacrifices to the tall cathedral that guarded the square. But not today. The old widow from Aÿ stood disconsolately by a couple of fraying baskets. Her straggly parsley had bolted and the meagre handful of mouldy onions should have been pickled long ago.

The haggard jam lady from Allers-Villerand was there, as always. Nicole might only be eleven, but she prided herself on noticing and that jam hadn’t sold for the last three markets. She knew because the lady had spelt strawberry wrong on this batch and anyone who could read was too polite to say.

She didn’t recognise the man from the butcher’s stall selling skinned rabbits on the other side of the square. Their raw bodies were topped and tailed, with furry heads and paws, bloated flies drooping over them like drunks.

‘Xavier!’ Nicole had spotted her friend standing next to the rabbit stall chatting with a gaggle of mates. She’d know him a mile off, with his compact frame and wiry black hair and she had hoped she would see him here. He would love the treasure she had in her pocket, a shiny green beetle, iridescent like a jewel.

He pretended not to hear her and arced a gob of glistening spit onto the cobbles. She was impressed.

He had been her playmate until her body made her different from him. She missed him now she was at school and he had to work. So why wasn’t he at her papa’s wool mills today?

‘Xavier, look what I found!’

He ignored her, so she marched closer, hand outstretched to show him the beetle.

‘It was on the rose bush in Monsieur Moët’s vineyard.’

Xavier smiled, but then remembered he was with a crowd of mates.

‘So what?’ he sneered. ‘What the hell is it anyway?’

‘Everyone knows it’s a rose beetle, you stupid grape-eater,’ she countered, smarting at his betrayal.

Xavier pretended not to care, but Nicole could tell he did by the way he sniffed and tossed his head. Grape-eater was the worst insult anyone could give in a wine-grower’s town, what they called workers from the Marne Vallée who didn’t know anything about vines, and ate the profits.

‘Aristocrate,’ shouted one of his friends, like it was a dirty word.

‘Leave her. She’s just a kid.’ Xavier jerked his head at Nicole. ‘Get lost, laide.’

Xavier had always been kind and he probably meant to be now. But the ugly – laide – stung. He constantly teased her that she was so petite she’d snap, and that her grey eyes were like a wolf’s rather than a girl’s and her reddish blonde hair looked like it was going rusty.

‘You don’t own this square,’ she snapped.

‘We do now. Va te faire foutre, aristocrate,’ the mate shouted. Fuck off, aristocrat.

‘I am the same as you,’ she protested, holding up her fists, flashing her pale eyes in fury. She might be small, but she was fast and strong and equal to any shouty boy. Damn that her mother had twisted her hair into stupid girly ringlets for school, today of all days.

Xavier pushed her. ‘Are you stupid? He’d crush you like a bloody ant.’

‘Fighting little girls, young man?’

It was the Comte d’Etoges looming over them, all the way from the château! His red silk coat blazed in the sun in stark contrast to the drab workers in the square, who glowered menacingly at him.

The Comte twisted Xavier’s arm behind his back. It looked like agony, but Xavier didn’t wince and Nicole was glad.

‘Apologise to Mademoiselle Ponsardin, you stinking little ruffian.’

The Comte pulled Xavier’s arm higher until Xavier turned ashen with pain. Nicole was scared he’d wrench his shoulder right out.

‘Sorry,’ he said, grimacing.

‘And you. Act like a lady, not a street urchin.’

Street urchins beat ladies any day. ‘Let him go. He was helping me,’ she said.

‘Know your place and assert your natural authority, young lady, or this rabble will imagine they are the deserving poor and demand justice. How old are you?’

‘Eleven.’ She refused to add ‘sir’.

‘You’ll learn. Give an inch and they’ll take a mile.’

He stomped off and Nicole pulled a face behind his back to impress Xavier, but he was already returning to the stall to stuff a rabbit in his sack. The butcher didn’t ask for any money and Xavier looked ashamed. Then she understood – the rabbits were alms for the poor. She wished she hadn’t called her friend a grape-eater.

Around the square, the red geraniums in the urns were neglected and withered, the hou

ses were crumbling and the paintwork was peeling. Crops were dying in the fields again this year. Nicole couldn’t remember a year when there’d been a celebration at harvest time, nor a big creamy moon lighting a magical evening of dancing, like she had heard about in the old days. Every week, the whole town prayed for a good harvest, but God wasn’t listening. This was why they were rioting in Paris, her father had told her. The aristocrats were stuffing themselves while the workers starved. Queen Marie Antoinette was so stupid, she’d offered cake to the poor instead of bread.

But Papa hadn’t told her the most gruesome part. Xavier had told her about that in graphic detail. The workers in Paris were going to rise up and round up all the aristocrats, take them to the Place de la Revolution and chop their heads off with a gruesome new thing they’d invented called the guillotine. It could efficiently kill ten aristocrats an hour, Xavier had told her, a big blade that slid down a frame and did the dirty deed, with aristocrats lining up one after the other, witnessing the death of their fellows and family before getting the chop themselves. Nicole had shivered, wishing he hadn’t told her, and hoping it wasn’t true.

She looked down at her dress, almost the same red as the Comte’s jacket, coloured with the kind of rich dye that the people in the square could never afford. Would she herself be counted as an aristocrat? But it was a fact that the king and queen weren’t in charge any more. The world was different and she felt frightened, even here, in her square.

She wished she’d gone to school after all, but the cathedral bell began striking. She would be too late and the nuns would tell Papa, so she might as well make the most of the trouble to come.

On the ninth toll of the bell, crowds of people filed into the square to queue at the rabbit stall. Most were country people, too poor to be regulars in this part of town. The butcher doled out one rabbit each. Some had sacks, others wrapped them in their aprons, a few didn’t have enough fabric to spare and held the meat by the ears. She watched for a while, then ran to the bakery.

‘Nicole! No school today?’ said Daniel, the baker.

‘The coin landed on tails,’ she lied.

‘Again? Tut tut. The nuns will cane the skin off your knuckles. Let me see?’

She held out her hand and showed him the welts from the last market day she had played truant.

He handed her a religieuse, a big, round choux pastry with a smaller one on top, filled with cream and topped with chocolate to resemble a nun. ‘Here, you can pretend you’re biting their heads off.’

She bit hard.

Daniel’s wife, Natasha, gave her a snowglobe to shake, a world of glittering frost and gilt ballrooms. Natasha was willowy and dark, with sallow skin and knowing brown eyes. She wore dirndl skirts edged with stitched patterns and symbols, like a Romani, and best of all she was from Russia, a world away from the little town of Reims. Nicole loved her stories of far-away icy wastelands and golden domes.

‘Delicious.’ Nicole grinned with her mouth full, when something splintered the boulangerie window and shattered it to the ground.

‘Ach,’ screamed Natasha, tracing figures of eight in the air as the patisseries were pierced with shards.

Daniel scooped a rock from the bakery floor and stormed out, waving it in the air. ‘Who the hell threw this?’ It was the stone hat from the king’s statue.

Outside, the old widow was on her hands and knees scraping spilt onions back into her baskets and the jam lady screamed vengeance for her smashed jars.

Three men straddled Nicole’s lucky statue of the king and the horse, bashing at it with hammers. They knocked off the easy bits first – the horse’s ears, the king’s foot, a length of his sword, egged on by a gang of men who were using the spoils as missiles.

‘Not the horse!’ Nicole yelled.

‘Hush! Get back here, you’ll get hit!’ Natasha urged, ushering her behind the counter and wrapping her in her skirts.

Amidst the chaos, the queue at the rabbit stall was still going. Muddy workers from the field, widows in black headscarves, barefoot, skinny children with grown-up, scabbed faces. The square was so busy now that she’d lost track of where Xavier and his friends had got to.

A gunshot ricocheted around the square. The queue froze, a child howled and the butcher dropped the rabbit he was holding. The three men slid down off the statue and slinked behind its broken flanks.

‘Nobody move!’

The Comte d’Etoges was back in his flashy silk jacket, this time at the head of a battalion from his private army, who fanned out into the square, blocking all the exits. A group of soldiers wrestled the three statue destroyers to the ground and handcuffed them. A roar of protest tore through the crowd.

The Comte’s powdered wig and white face made him look like a menacing ghost and his cool, fixed expression was more disturbing than the crowd’s anger. His voice boomed over them, but he wasn’t shouting.

‘These vandals have committed a crime and will rot in jail for the remainder of their days,’ he said calmly to the desperate bystanders who’d been innocently queuing at the rabbit stall. ‘The rest of you are charged with poaching and will be severely punished.’

‘They’re hungry, you can spare them,’ Daniel shouted back.

‘Hush, milaya,’ Natasha beseeched her husband, hugging Nicole to her.

‘Name, scum?’ said the Comte, pointing the gun at him.

‘Daniel. From the boulangerie.’ He pointed to the smashed window.

Behind him, the priest creaked open the big cathedral doors and raised his hand.

‘Calm, in the name of Jesus!’ he bellowed.

Someone threw the horse’s ear at the priest and ran before a soldier could react.

Nicole screwed her eyes tight and waited for lightning to strike. The gargoyles would come to life and scream hellfire and they’d all burn for eternity for throwing stones at the priest. But God did nothing. The priest staggered back inside and slammed the church door. He was supposed to be in charge. Coward!

The Comte waved his gun at Daniel. ‘You, tell your comrades to disperse. Those rabbits are stolen goods.’

Daniel folded his arms. ‘These people are starving. The rabbits are already dead and decaying. They’re no use to you.’

‘Daniel, look out!’ shrieked Nicole as the Comte cocked his gun and shot.

The baker slumped, clutching his chest. Natasha flew to him, black hair streaming. She tore open his shirt and screamed, her hands slippery with blood.

Don’t die, don’t die, prayed Nicole, cowering behind the counter.

Natasha cradled him, ripped her skirt and pressed wads on the wound, but blood leached over her fingers. The old widow from Aÿ untied her scarf to make a bandage and limped stiffly towards them.

‘Don’t move!’ the Comte bellowed.

She halted, face tight. Everybody stopped dead.

Natasha was alone, keening like a madwoman in the sudden silence. Nicole sneaked out from behind the counter and ran to them.

‘Bordel de merde, stop I said!’ the Comte yelled at her.

A bullet shot past her ear and the crowd roared again. She flung her arms around Natasha’s neck. The air was so thick and hot, it hurt to breathe. Daniel’s eyes were open, but unseeing.

‘Is he dead?’ she whispered.

Natasha didn’t answer.

‘Take aim!’ ordered the Comte.

The soldiers shouldered their guns and pointed them at the horrified crowd. Surely God would intervene now? The cathedral door stayed locked.

Natasha cradled her husband in her lap, appalled, a pietà in the square. Nicole huddled behind her back.

‘Go home and don’t look back, little one,’ said Natasha steadily.

Nicole got up, straightened her skirt and walked slowly towards the Comte. He kept his gun on her, adjusting the sights as she came closer.

‘You killed him,’ she spat.

‘These people are thieves and that, little girl, is called justice.’

‘I will never forget,’ she said quietly, ‘and neither will they.’

She kept her eyes on him and walked on. She belonged here, with Natasha and her dead husband, with the workers and their scraps of stolen meat. She ducked behind the pump in the rue de la Vache and turned to watch. She would be their witness.

‘Let this be a warning,’ shouted the Comte. ‘Go back to your work. Anyone who defies the rule of law will die like your friend. Men, let’s go!’

The statue defacers were bundled into a cart and beaten with rifle butts as they were driven off, defenceless and handcuffed. The soldiers melted away and the Comte followed in his carriage, wheels crunching gravel.

The widow from Aÿ was the first to reach Natasha. She crossed herself for Daniel and whispered in her ear. Natasha nodded and allowed two men to carry Daniel back to the bakery, holding his hand to her cheek. He looked heavy, like his soul was gone, vulnerable, bloody and raw as the dead rabbits.

Men slid off their caps, women bowed their heads and the crowd stayed rooted in respectful, stunned silence until Daniel and his makeshift cortège disappeared inside. Then the rabbit queue erupted, hurling the table of meat in a swarm of flies and heaving over the urns of withered geraniums.

Peeking from behind the relative safety of the pump, Nicole saw Xavier rip a torch from the blacksmith’s, igniting a hay bale that sprung wild flames in the stifling heat. The crowd smashed the windows of Moët’s wine merchant, poured stolen brandy on the flames and chucked in the bottles, glass popping and exploding in the fire. A new gang set upon the king’s statue, more organised this time, a foreman yelling instructions, until it toppled to the ground and crumbled into pieces.

The French House

The French House